HRO: Adventures of a Humanoid Resources Officer

Shocked! Shocked, I tell you!

Most recently, I’ve been working to improve my animation skills. Mostly with the Adobe suite of software. Adobe AfterEffects is similar enough to Adobe Illustrator — a package I have had a lot of experience using — that I grasped the underlying mechanics quickly, and then spent a ton of time trying to refine and get the software to do some cooler stuff. it’s been a wild ride. Eric and I also spent some time last year working on Rhubarb integration, which is an awesome tool. Plug in eight images of mouth position art and an audio file and Rhubarb will automatically create the mouth movements to make the text look more-or-less right. Which is way easier and less time-consuming than the more traditional methods of lip syncing.

Of course, the downside of getting to learn all this new stuff is that we are sometimes ill-equipped to reasonably predict how long some of these novel tasks might actually take to perform. There are times when this lack of foreknowledge isn’t a big deal — a day or two lost here and there — and sometimes it is a big deal. Take the animation I was talking about in the last paragraph. We had allocated two months to create, animate and lip synch about 97 pages of dialogue. Which, now that we’re in the thick of it, turns out to have been wildly optimistic. So, despite good intentions, a rock-solid work ethic, a plan to streamline and re-use animation assets and the illusion of clear-headed planning, it looks like our production pipeline has temporarily gotten the better of us.

This is all a long-winded way to say that we’re probably not going to meet the original projected December release date for HRO (shocked! shocked!) It’s a little disappointing, but it’s also a little exciting. Because the final product will only be richer for the extra time and care that a solid execution will give us. We hope you’ll bear with us and we look forward to keeping you updated on our progress in future posts.

Fixation Without Representation

In this respect, HRO has some advantages over the Jane Austen project we produced a few years ago. Some of the inspirations for this project were pioneers in diverse casting and racially-aware storytelling as early as the 1960’s. The futuristic setting and the perception that sci-fi programs like the original “Star Trek” weren’t “serious television” gave visionaries like Gene Rodenberry some cover to push the boundaries. And they used that opportunity to bring ground-breaking social change into our living rooms hidden behind paper-maché rocks and rubber masks. But even they weren’t grappling with doing justice to the fullness of human society back then. It would be decades before the first LGBTQ character showed up in the Federation universe.

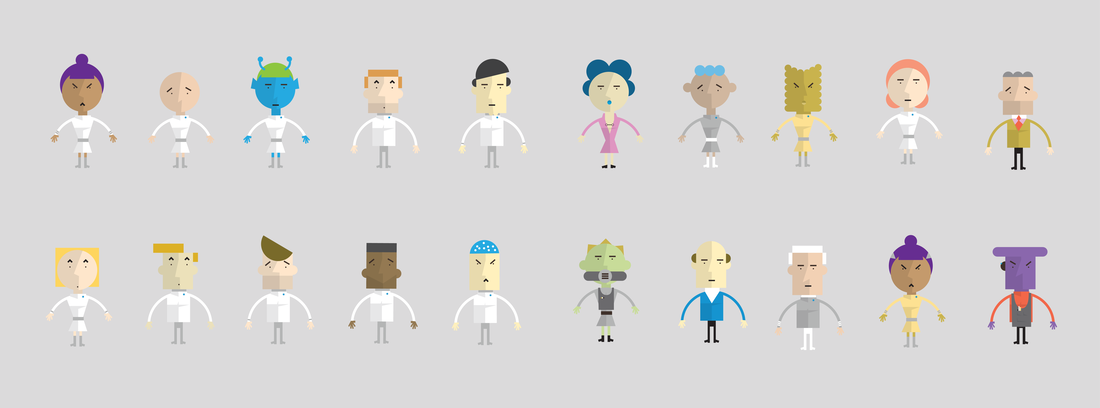

So it was with a sense of joy and purpose that we set out to populate our science fiction universe with as broad a cross-section of humanity (humanoidity?) as we could muster. Of course—in a game like HRO — there was the question of aliens. We had conversations about how the aliens in the game fit into the calculus of balanced representation and whether they could be misinterpreted as stand-ins for minority groups we didn’t explicitly include (spoiler alert, they’re not).

What we didn’t see coming was the effect this would have on our cast size… In the end, the final tally was forty-two characters, including recurring cast members and “guest stars.” Great for representation! Terrible for cost-efficient voice-over actor casting! Generally, a studio of our size would plan to hire six or seven actors to each voice multiple characters. Efficient. But tough to execute if you’re also looking to make opportunities available to a diverse range of cast members to voice your diverse cast of characters. In the end, we found a delightfully flexible pool of actors who — in addition to being amazingly talented — were willing to be hired for smaller chunks of time each so we could bring in more total voices.

We hope you’re as excited as we are to play in a universe where everyone has a seat at the table. The ship’s conference room table that is. Where the senior staff is gathered to brainstorm last minute schemes to save the ship from being sucked into — say — a Dark Grey Hole whose trademark Crushing Gravity Well would surely kill them all! Yay diversity!