Silk

Silk is About... Glorantha

So I knew I wanted to make this tribute game about exploration, but I also didn’t want to pass up the opportunity to experiment with radical unexplored possibilities in narrative design, and for this I had another influence: King of Dragon Pass. I had always regretted ‘missing out’ on RuneQuest, possibly the only classic 1980s RPG that I never got to play. King of Dragon Pass let me participate in Gregg Stafford’s extraordinary game by having been set in the world of Glorantha and being, in a very tangible sense about Glorantha. To play King of Dragon Pass is to enter into a fantasy world that’s not like any others out there... it’s more Bronze Age than Medieval, it’s a world where gods and spirits are tangible and pressing in on mortal life. David Dunham’s game is an incredible achievement, one that came to my attention because my colleague at International Hobo in the 2000s, Ernest Adams, waxed lyrical about its achievements in narrative design.

But what I really fell in love with in King of Dragon Pass was the Clan Ring, the set of people who advise you as to what decisions you could be taking as the game progresses. I became obsessed with how this worked, and dug into its designed systems and internal language (OSL), becoming ever more convinced that what was ‘just’ another clever extra feature in that particular game could become the central element of a narrative design that was based upon an entirely different kind of play. Perhaps, the kind of play that would see the player striking out across three million square miles of wilderness....

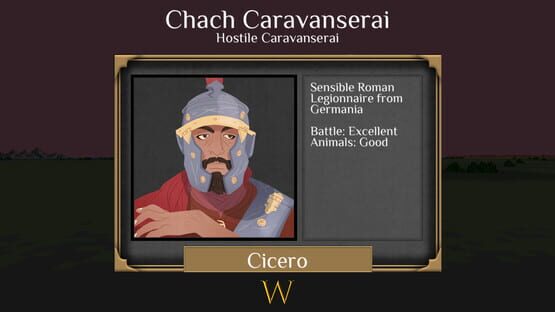

The Clan Ring in King of Dragon Pass became the Advisors in Silk. They’re your party, you hire them to your Caravan, and once you hire them they’re with you until the end of the game. That wasn’t how the design began – for a while, the paper design allowed the Advisors to die if they failed a skill check spectacularly. But as time went on, I came to realise that what I was doing with Silk in terms of letting the player explore the cultures of 200AD (just as King of Dragon Pass lets you explore the culture of Glorantha), was stronger in some ineffable sense if your Caravan was more than just a set of interchangeable pawns. The Caravan is your family in the game... and by necessity, it’s going to be a family of misfits, just like every party of adventurers in RuneQuest. That’s something that speaks to me as a player of games, and a lover of the strange. It’s why even though Silk is set in 200AD, it’s also in a strange but understandable way, about Glorantha.

Silk is About... 1984

One of these stories is well known... David Braben and Ian Bell made Elite, which with its vast feeling of player freedom would go on to directly influence Grand Theft Auto, and thus give birth to the open world genre as we now know it. But even that’s not the whole story, because Elite is a descendent of tabletop role-playing games, specifically Traveller and Space Opera, and it was the infinite agency of the tabletop RPG that inspired Elite’s radical approach to digital agency. It’s always a mistake to think videogames sprung into life from nowhere... they flowed down the river of artworks like everything else.

Two other great precursors to the open world game that came out of these two years are both from 1985: Andrew Braybrook’s Paradroid – which I still suspect was an influence upon Grand Theft Auto’s car stealing (although I have not yet proved it), and Paul Woakes and Bruce Jordan’s Mercenary, that took Elite’s wireframe world and made a fantastic story out of it (Surely the faction system in the original GTA was inspired by this game...?). Paradroid is actually my favourite game of the last century, but I don’t feel quite the sense of debt towards it as I do to another 1984 classic, perhaps because I got to work with Andrew Braybrook and Steve Turner in the waning years of Graftgold, and so our stories already intersected in some way.

The last of the four harbingers of the open world is Mike Singleton’s The Lords of Midnight, the best adaptation of The Lord of the Rings to never have had the license. Singleton was not influenced by tabletop RPGs as far as I can tell, but was just interested in how to take the two threads of Tolkien’s epic – the adventure story and the epic war – and represent them in the 48K of the ZX Spectrum, Europe’s most iconic home computer. I was spellbound by The Lords of Midnight, even though it was actually terribly difficult to play, and even more difficult to play well. My appreciation of what it achieved grew when I started giving talks about the history of games, and peaked when I finally sacked Ushgarak (let’s not call it the Dark Tower of Mordor...) in Chris Wild’s outstanding port of the game.

Singleton did not rest on his laurels. The open-world-before-open-worlds concept was revisited in a sequel, Doomdark’s Revenge (which also has a fantastic port by Chris Wild) and later in Midwinter and its sequel, games that moved into polygonal 3D and were equally astounding, perhaps even more so, since they attempted the immersive presence we now expect from first person games before the hardware was in any way up to the task of rendering them. But there was just something about that square-based world in The Lords of Midnight that maintained its magic. It’s a mystical wonder that can also be found in Eye of the Beholder and The Bard’s Tale, which also built their world on squares, although both had so much more computational resources available that they cannot possibly count as the technical achievement that Mike Singleton’s classic was.

I felt a debt of honour to him. I don’t really know why, but I always have. In the 1990s, when I was working on the Discworld games, I tried to make a game in that style, but it was impossible to make the argument for it then. It’s not that much easier now, to be honest! But at least now we have a thriving indie community who sometimes welcome the strange and wonderful into their hearts. So I made Silk, to pay off that debt to Mike Singleton. It’s why even though the game is set in 200AD, it’s also inextricably about 1984.

Silk is About... 200AD

Silk is about 1984.

Silk is about Glorantha.

Silk is about religion.

Silk is about Brexit.

Five seemingly contradictory statements, all absolutely true. The fact that all these claims are true doesn’t spring from any conceptual gymnastics, it flows naturally from the way I came to design and ultimately implement Silk, with the incredible help of Nathan (the programmer) and Jamie (the artist), and many others (like Becky, the portrait artist; Chris, the composer; and Patrick and Sean, the producers).

That games are about things doesn’t sound controversial, but in an odd way it is. That’s because the entertainment value of a game (or a film, for that matter) is the moral value we elevate above all others for them – provided a game entertains, all other priorities are rescinded. That’s why games are a multi-billion dollar industry today: not because they are a vibrant, extravagant, hugely inventive artform (although they are), but because they entertain. And who doesn’t like being entertained? By definition, it’s something we all want.

But it’s not enough of a reason to make a game like Silk, because the people who might be entertained by a game like this are not the same people who are going to be entertained by, say, Grand Theft Auto, even though the GTA franchise and Silk have their roots in exactly the same places: the British games of 1984 and 1985 that invented the open world before anyone had thought of calling it that. No, Silk is a niche game... it’s a game for players who are looking to be more than just entertained, who are willing to be challenged to take upon a new way of thinking, one quite different from those that most games present us today.

We should start by acknowledging that this is a game about 200AD. This is a time period I’ve always been enraptured by... the Roman republic has mutated into the Roman Empire, bringing the seeds of its eventual downfall. Thousands of miles east, the Han Empire are about to lose control of China as it slips into the vicious civil war known as the Three Kingdoms. And in between these two ends of the Ancient Silk Road are two other empires that people just don’t talk that much about – the Parthians, who are Rome’s bitter enemy (and whom Rome never convincingly defeated), and the Kushan Empire who rule what we now call India with a cosmopolitanism that is quite astonishing for a time two millennia before our own. To play Silk is to visit 200AD. That’s the player experience we’re offering, over and above any other themes I might have weaved into its narrative design.

I’ve been writing Designer’s Notes since 1993 for every game that I can definitively call ‘mine’ (without denying my immense dependence upon those who work alongside me). I was inspired to do so by Sandy Peterson, the designer of Call of Cthulhu (and level designer on Quake), who first made it clear to me that pretending you’re not influenced by other people’s designs is pure arrogance and folly. In this five part series of Designer’s Notes, I want to look at five things Silk is about. The first, as I’ve just discussed, is 200AD. I’m not going to say too much about that because if you want to know about 200AD you should play Silk – short of a time machine, there’s no other way of experiencing it! But the other four thematic influences upon Silk – 1984, Glorantha, religion, and Brexit – those are things you probably aren’t going to get out of just playing Silk. They require me to tell something of the story behind the game, and that’s what Designer’s Notes are ultimately about. These are the notes I want to make about the most personal game I’ve ever made.

I hope you’ll join me for this journey.