The weirdest part of the story is that, for the most part, support for large team games came about accidentally. The rest of the Zero-K design philosophy just happens to inherently let teams have a large number of players. From time to time we added features aimed at large games, but most of the work is done by principles covered in previous cold takes. We could have deliberately removed large teams, but the attempt would warp the rest of the design, and it is not like they are hurting other game modes. Small games, down to 1v1 and 2v2, work fine, and the way I see it, supporting more game modes is good.

The bulk of the work is done by Fight your opponent, not the UI, plus the realisation that players coordinate with their team via the user interface. Essentially, cooperation within a team should be free of artificial limitations or hoops to jump through, in much the same way as any other action in the game. Zero-K contains simple examples of cooperation UI, such as the nuke indicator that tells players where an allied nuke is expected to land, but not fighting the UI goes deeper than that.

Zero-K is the game that designs the stupidity out of units and uses designs weapons using unattainable ideals, and we take the same approach to cooperation. Like units, players have abilities that influence the game, and we consider it a failure if the mechanics of the game force players down the route of boring and arduous use of the UI. So while most games would happily add a nuke indicator, few would go the extra step of excising fundamentally anti-cooperative mechanics to the extent that we do.

We inherited key player abilities, namely the ability to freely share units and resources, from Total Annihilation. This is a fairly standard function for RTS games, but the implications are far-reaching, and Zero-K has a penchant for taking ideas to the extreme and biting the resulting bullets. The issue with sharing is that sharing UIs are invariably some of the worst found in RTS. They tend to resemble big spreadsheets of fiddly buttons or sliders, which is not what we want in an RTS. So contact with this UI should be minimised, which relegates sharing to an almost "theoretical" ability, one that the game is designed around, but which players should rarely manually invoke. This generalises to the principle of the irrelevance of ownership:

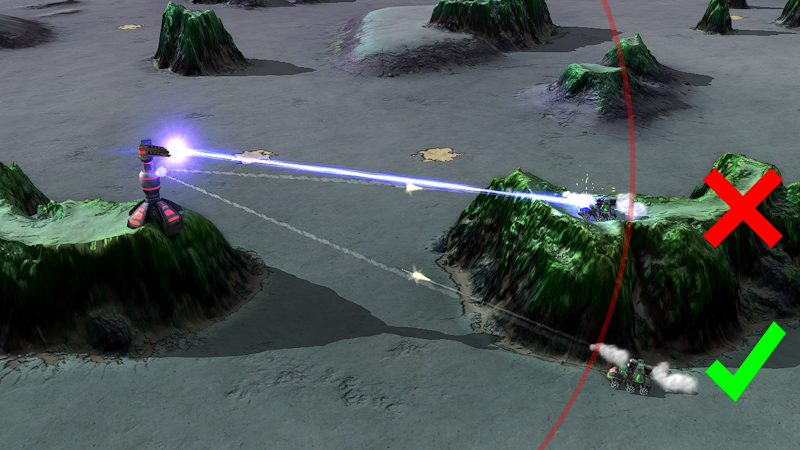

Nothing in the mechanics of the game world is permitted to depend on the details of ownership within a team, because then players would be incentivised to touch the unit sharing UI to gain an advantage.

Few games use this principle, since it is automatically violated by player-specific upgrades. Even within the TA-lineage, Supreme Commander lets units of the same player shoot through each other, but not through allies. Even Zero-K violates the principle, since unidentified radar dots reveal team colour, which can let the enemy guess the identity of unseen units. This is something I have wanted to be able to turn off, but it requires engine work, and to walk back the extremism a bit, dot colour may well improve the game.

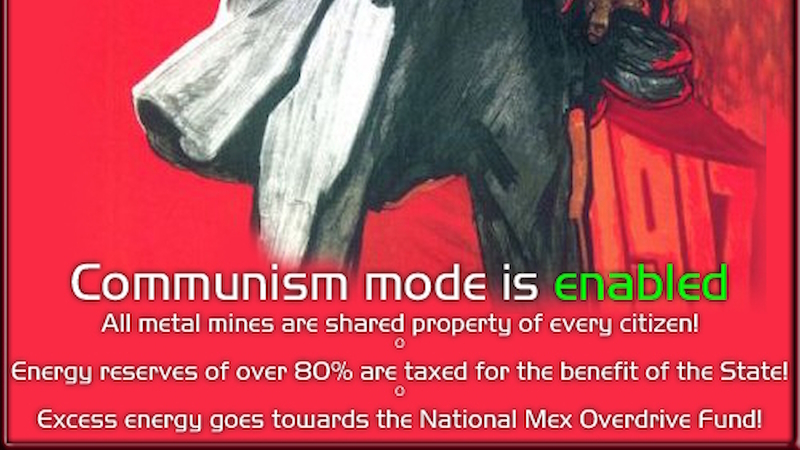

The principle of irrelevance of ownership sounds restrictive, but it is also quite freeing, and we were not going to add global upgrades regardless. A key implication of the principle is that resource income can be distributed arbitrarily within a team, without any theoretical impact on in-world game balance. In practise this let us fiddle with income sharing to "simulate" cooperation among strangers on the internet, which is part of what allows such large team games to work. For example, income from metal extractors is shared evenly between everyone on the team, which was called communism mode in early Complete Annihilation. Communism evolved alongside the rest of the game, and quickly became integrated with overdrive, since the overdrive formula benefits from shared resources.

The theoretical justification for communism is that securing territory is a shared effort, and much harder than merely building a metal extractor, so the team shares the benefit. The practical justification was more important at the time though, since we all had experience with people arguing over metal spots in Balanced Annihilation, which could escalate to teamkilling. A secondary effect in BA was the limited map pool; players tended to play a small set of maps, where everyone understood the meta of spot ownership, in part to lessen the potential for arguments over resources.

It is worth mentioning that I snuck an assumption into communism: that players want to cooperate. What if people want to keep their income to themselves? This gets at the core of the design: we assume that the team wants to cooperate, teamwork is the default. If players want to argue and destroy each other's buildings, then they might not find support for these actions in the UI. There is also a bit of a paradox here, as anyone who has played a team game with a range of skill levels can tell you: who owns what is actually very important. But instead of trying to judge the worth of each player, we opted to make a game where part of the skill is in being a good teammate, rather than rolling over the weaker members on your team as you grow your own personal empire.

Communism solved the metal spot arguments and opened up the map pool, but it suffered from the free rider problem. Some players would skip building metal extractors all together, hoping that their teammates would pick up the slack. Full communism was also not great at incentivising overdrive, even when it would significantly benefit the team. So we added rebates. For example, metal extractors refund 80% of their cost to the player(s) that built them, over a few minutes, in the form of a slightly increased share of the income. Energy structures offer a similar refund of 60% from their increased metal overdrive income. The numbers have been tweaked over the years, since a higher payback percentage can lead to perceptions of selfishness by energy spammers. We even recently introduced payback for the first few Antinukes built by a team, as a social way to nerf nukes in low-cooperation situations.

Shared metal extractors also helped with the "Tabula Problem" caused by some rotationally symmetric maps. Tabula has high terrain on its North and South, that is easier to take and defend from the North-West and South-East respectively. Before communism, Tabula was typically won by the team that invaded the weak low ground from the strong high groud, before their opponent did the same on the other side of the map. The low ground just lacked the metal income required to mount a defense, without players manually sharing units or metal extractors. Tabula continued to play a bit like this since communism, the low ground still has poor terrain, but the extra income makes the defense fairer and more interesting.

Income sharing alone is not enough to make large games fun. For that we need the rest of Zero-K, primarily its unit and faction design. Our large number of faction-like factories lets players carve out a distinct role and set of units within the team, and factory plop lets everyone build a factory without "wasting" resources team. There was concern that the recent addition of factory plates would destroy this sense of having a role within a team, but the fear has not come to pass. If anything they seem to have improved team games by letting players take on a role they are not sure of, with the safety of being able to switch out of it cheaply.

The coordination feature that came closest to breaking the game was shared control mode, where players own and control the same set of units. The campaign has shared control, but it can also be enabled in team games via an invite system. The danger with shared unit control is that it can be powerful, but it is also quite annoying when someone else accidentally uses "your" units. This is the dreaded trade-off, power at the cost of fighting the UI, but the mode is barely used in public games. Tournament and campaign games are different, since people can communicate enough to avoid the downsides, and in these contexts it is a great feature.

As with many automation-type features, it is worth asking whether cooperation has been automated away. I think we are fine on this front; teammates send messages, flank, and otherwise help each other out. People still share the occasional unit to augment fronts that really need it. Mostly we have removed the excess UI interactions, and set a baseline level of cooperation so players can expand as much as they want without worrying about "stealing" metal spots. Perhaps the greatest benefit is too the map pool, as any map can be played with any number of players, for a really wide range of experiences.

This marks the end of the first series of cold takes. Twenty is a nice round number and it is time for a short break. Look forward to the next series starting in January next year.

Index of Cold Takes