Wanderlust

Wanderlust: Transsiberian has arrived at the station!

A new journey has begun in Wanderlust: Transsiberian. This new chapter in the Wanderlust saga is already available on Steam, and with 40% off. Check it out if you want to expand your grand adventure from the main game.

Being a standalone expansion priced at $4.99, not mentioning the launch discount, Transsiberian is also a good way to introduce yourself to the Wanderlust formula.

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1233420/Wanderlust_Transsiberian/

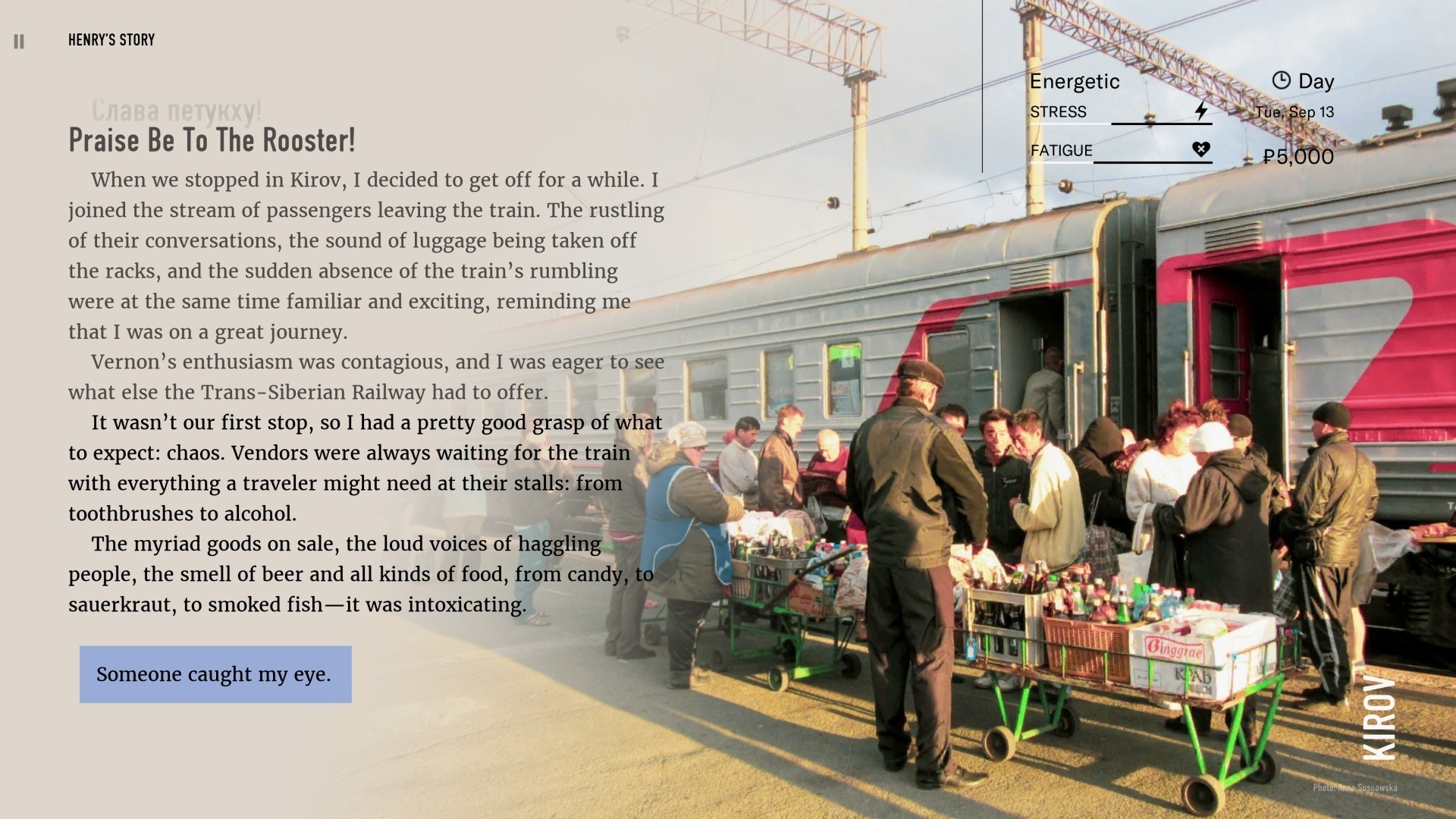

This tale follows two men who embark on a trip to the easternmost reaches of Russia onboard the longest railway line in the world. You are Henry, a professional photographer, whom some of you may remember from Wanderlust: Travel Stories. You can travel as you really would or try something different while soaking up the atmosphere of Russia.

Do you miss travelling? Give Wanderlust: Transsiberian a try, and have a good time!

[previewyoutube="u4HD2jh0Mlg;full"]

We're in the Polish Spring Festival Bundle

Here's the full list of games featured in the bundle:

- Darkwood, a new perspective on survival horror.

- Frostpunk, the first society survival game.

- Get Even, an action game with a mystery plot and groundbreaking visuals.

- My Memory of Us, a moving fairy tale about friendship and hope.

- Observer, a cyberpunk horror game starring Rutger Hauer.

- SUPERHOT, a first-person shooter where time only moves when you move.

- This War of Mine, a war game seen from the perspective of the civilians.

- Wanderlust: Travel Stories, a collection of travel memoirs in the form of an adventure game.

- We. The Revolution, a game that lets you play as a judge during the French Revolution.

These games have two things in common: they all come from Poland, and have been nominated to Polityka's Passports, one of the most important Polish cultural awards.

We're happy to see Wanderlust: Travel Stories in such esteemed company, especially now, when you can save on every single one of these titles.

Check out the bundle, and have fun!

EXPLORE THE POLISH SPRING FESITVAL BUNDLE

Wanderlust: Transsiberian is on its way!

We'll soon travel together again in Wanderlust: Transsiberian, a standalone new chapter of Wanderlust: Travel Stories! On April 9th, board the legendary Trans-Siberian railway and journey 9,289 km from Moscow to Vladivostok.

During this journey, you will get a chance to soak up the atmosphere of Russian wilderness, and clash with a vibrant culture as you encounter people as strange to you as you are to them.

We hope that for those of you who have already played Wanderlust: Travel Stories, Transsiberian will be a great way to expand the grand adventure. However, if you haven't played our game, it's a great way to introduce yourself to the experience.

This one hour-long chapter features everything you'd expect: rich descriptions, bespoke photography, colorful characters and lots of meaningful choices that change not only what you do, but also how you perceive everything around you.

If you'd like to support us, add Wanderlust: Transsiberian to your wishlist.

See you on the road!

Artur from Different Tales

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1233420/Wanderlust_Transsiberian/

Version 1.8 Available

Journey into the music — our Soundtrack hits the shelves!

The original soundtrack for Wanderlust: Travel Stories is here, and with more than 70 minutes of beautiful instrumental music, I hope it's going to take you to faraway places. Just turn up the volume and relax.

We are double excited for this release, seeing as your reviews often mentioned how much you've enjoyed the soundtrack during your playthroughs. We've teamed up with four composers to score the game—to make sure that all the main characters and stories have their own, unique identity. The OST features 23 tracks by Tomasz Kuczma, Robert Purzycki, Patryk Scelina and Igor Szulc. Check out the Main Theme below:

[previewyoutube="Dff4cw6mqj4;full"]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dff4cw6mqj4[/previewyoutube]

Click HERE to go to the soundtrack, close your eyes and let the music take you somewhere else.

PS. Get the soundtrack bundle for an extra 20% off, even if you already own the game!

All the best,

Jacek from Different Tales

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1224190

We won the award for THE BEST POLISH MOBILE GAME

Wanderlust: Travel Stories has won the Graczpospolita Award for the Best Polish Mobile Game of 2019!

We can imagine you saying: "Hold up, there's a mobile Wanderlust?" We haven't mentioned this here until now, but yes, there is an iOS version of our game. It's the full experience, repackaged and tweaked to make it 100% enjoyable on the mobiles.

This version has actually won an award for the Best Mobile Game before, at Digital Dragons' Indie Showcase. If you'd like to try it, you can find it on the Apple App Store.

What are the Graczpospolita Awards?

These are awards given every year by the gaming branch of Rzeczpospolita, one of the biggest and most respected newspapers in Poland, for the best games developed in our country. This year's other winners are: Blair Witch, Tools Up! and Cyberpunk 2077 (Most Awaited Game), so it's certainly good company to be in.

We are grateful for the recognition!

On the Uncharted Waters of Procedural Narratives

We knew from the very beginning that we wanted to have a marine tale in Wanderlust: Travel Stories, and we even wrote a draft of a chapter set in the Caribbean. Then, in October 2018, Mateusz Kubik, who was a researcher in our team and a skipper, sailed to the Antarctic on a brave steel ketch named Selma. He came back with a detailed account of his journey and a few memory cards worth of photographs, and we knew that our protagonists were heading towards much colder waters.

Introduction

There are two types of narrative content in Wanderlust: Travel Stories: scenes and flow. A scene was your default branching/interactive text you navigated and shaped by making choices. More on how we made the choices personal, see this post.

One of the cornerstones of our design was to make you feel like it was your journey, make you the traveler, not just someone who listens to a traveler’s story. And if there was something that we found in every travel story we heard, it was the meditative moments when you sit and watch the landscape roll outside the window. We decided to recreate those moments in the game, and we called the mechanism “the flow.”

This post details how we used a very simple procedural generation to narrate our heroine sailing through the icy waters of the Antarctic.

Go With The Flow

To recreate the moments of travel, we used a number of tools. The first was to take a degree of control from the player — in the flow, a map is displayed and text appears by itself, as the dot moves along the chosen path. Music and ambient sounds heighten the feeling of movement. Choices appear from time to time, allowing the player to shape their travel and literary experience: enjoy the views, interact with fellow travelers, read, get lost in thoughts or maybe just sleep?

When preparing Henriette’s flow in the Antarctic story we faced a unique challenge: we wanted to relay a truth about sailing and use Mateusz’s input experiences to the fullest while keeping the story tailored by player’s choices and interesting.

Notes From The Frozen Seas

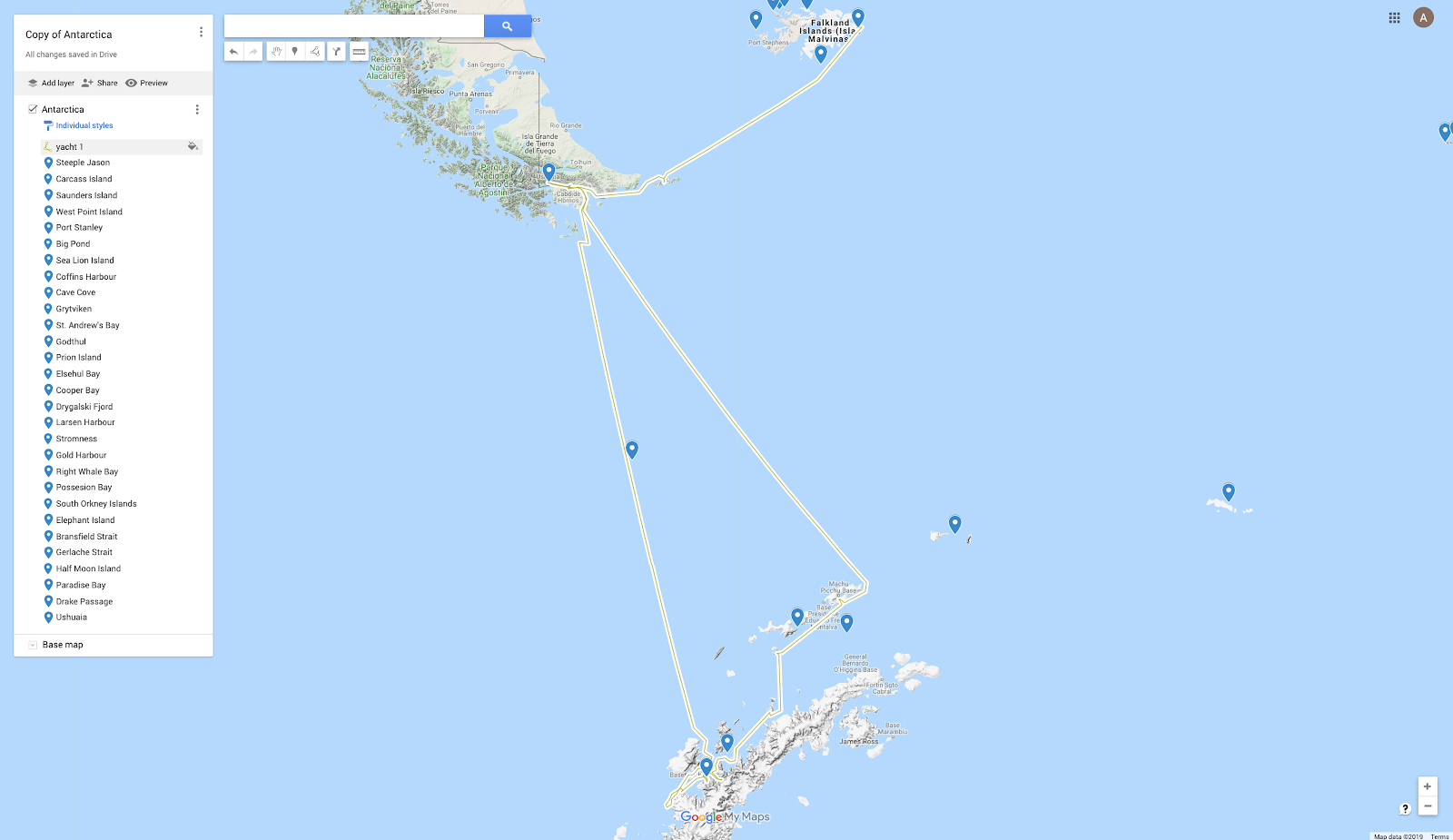

We started with the map, detailing the boat’s route and estimated times for every leg of the journey. That was relatively easy to bring into the game, although choosing the right cameras took some time. After some experiments, we decided for one place, where the player’s decisions could cut two days of travel, but apart from that, we decided for a set speed of the boat.

We start on the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas, sail west, then south, and back to Ushuaia.

The life onboard is ruled by the changing of watches, and we got the schedule described firsthand. Mateusz prepared a handy table explaining how watches changed with a crew of eight people, and what each watch was responsible for. We started with that.

Life on a boat: many occasions to get cold, little time for yourself.

Apart from the watches, we wanted to show all aspects of life on a boat: the views by day and by the short polar night, the weather, the time spent below deck, the technicalities of sleep, the food and the chores.

Simulated Boredom

I started with writing a convoluted script in Ink, that was supposed to watch the schedule and switch between the flow depicting the views and the description of watches at the appropriate times. It knew when your next watch was, and whether it was a galley or a navigation watch. It had those neat extra sentences connecting the views and the work into one narrative. Sometimes it was even aware that you needed to eat and added the meal description into the flow. We tested it, and to my dismay, the result was utterly boring.

The problem soon became clear: to simulate the schedule we needed a new text every hour, an hour and a half. For a 64-hour-long sailing, it amounted to at least 42 lines on the screen. With a new line appearing every 12 seconds, it amounted to almost nine minutes of staring at the screen and listening to the howling of the wind and the flapping of sails.

Quite accurate if you wanted to show the inevitable, boring side of sailing, but also way too boring for our readers. After some testing, we found an acceptable ratio: 16 lines for 64 hours, one line every 4 hours. With watches lasting three hours, it became clear to us, that simulating the sail watch after watch was not an option.

The whole process would have been easier if I had thought more about our core design principles for the game, instead of just having fun with writing convoluted Ink scripts. From the very beginning, we had this idea, that we wanted to simulate not the boring parts of traveling, but the feelings and emotions of a traveler.

Which, again and again, proved a good idea for the game we were working on.

A Sailor’s Life

In the end, we made every leg of a journey into a personified journal entry: Henriette talking about her experiences on the watch, of the views she saw, of the life on the boat. As in many other places in Wanderlust: Travel Stories, we prepared the structure and let players fill in the details in the way they liked.

Let me show you how the flow in Antarctica worked.

And We Sailed…

Every leg of a journey started with an intro, sometimes differentiated by the character’s mood.

The situation is the same, Henriette’s perception differs.

In most of the scenarios Henriette started on the deck of the boat, only deep in the Antarctic she started the journey sitting in the galley. From that moment on, we let the player and the scripts compose most of the narrative.

We usually started with describing the views or scenes from the galley — those are described in the next sections. Sooner or later, a watch started.

On My Watch

To ensure a smooth transition, we wrote a number of connecting sentences, accounting for what Henriette was doing at the moment, and for whether it was a navigation, or a galley watch. We used similar sentences to end the watch.

If Henriette is asleep, the watch will be introduced with different phrasing.

We wrote new variants until the repetition was no longer visible to players.

Henriette’s impressions were taken from Mateusz’s notes, cut into short phrases, and sentences and randomly rebuilt during the game to create a varied array of comments.

A random collection of snippets from a sailor’s life.

It’s hard to convey the isolation you feel at night in the middle of a sea, but we tried.

But the part of the watch most noticeable for the player was the choice about whether to talk to Chris or just focus on sailing. Focusing on the boat made Henriette a better sailor, while conversation made her better with people — both paths finding their conclusion in the story’s final scenes.

The nature of the conversation changed based on the mood Henriette was in: from complaining about an obnoxious crew member, through discussing the climate crisis, to a collection of dad jokes that I decided not to quote here.

To feed nine people over five weeks of sailing you need a ton of food. Literally.

If you wondered, the meals described in the game, are based on what Mateusz really cooked.

Beautiful Cold Seas

After the watch, the player could decide whether to say on the deck or to sit in the galley. One option more tiring, the other allowing for a moment of rest. One showing the views outside the boat, the other snippets from the crew’s daily routines. When it was night or Henriette was very tired, sleep also became an available option.

Depending on the player’s choices the game reached different boxes filled with sentences for every occasion and put a narrative together. Here and there we procedurally added comments reflecting Henriettes current mood.

Every leg of a journey had its own views for a day and a night (with the night getting shorter the more south the boat sailed), while the scenes under the deck consisted of micro-stories developing at their own pace.

Chris always reads a book about Antarctica, but the title comments on player’s previous choices.

Where possible, we tried to comment on the player’s previous decisions or the character’s current mood.

We Anchored…

Every flow ended with a sentence introducing the next scene.

Almost every sentence on the screen depends on the player’s input.

All in all, those mechanisms and choices created a rather smooth narrative about sailing from point A to point B.

The Final Touches

When we put it together we noticed that we still have a number of beautiful pictures unused, so we added an extra choice here and there, that (if chosen) triggered a small scene, breaking the monotony of the flow — just like a beautiful view breaks the monotony of a lonely watch.

Choices may vary, depending on the circumstances.

Penguins, watching you watching them.

Summary

As you can see, working on our documentary input material we went from an hour-to-hour simulation to a more journal-like approach. Most of the narrative in the flow parts of the story is procedurally generated, paragraphs constructed from smaller parts or randomly chosen from different bags. The system decides which bag to choose, based on the player’s input — both explicit (choices) and indirect (Hentriette’s mood), the watches’ schedule, time of day, and location. Sometimes we used connecting sentences, ex. “I was woken with a shake. It was time to start my watch.” to keep the narrative flowing.

The main choices in the flow, from the story perspective, are about what is more important for Henriette: sailing and the views, or relations and her crew-mates.

The texts are composed of actual notes from sailing through the Antarctic, and we hope the overall narrative is credible enough to show you a truth about sailing and personal enough to keep it interesting.

As my mother said, reading through Henriette’s story: “I would never go there, it’s way too cold… and yet, people do.”

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1051410/Wanderlust_Travel_Stories/

Christmas, the Polish way

For many people around the world, Christmas is a special time of the year. However, unlike in most countries, in Poland, we start celebrating today, on Christmas Eve.

Right about now Polish families are having their festive supper after a day of fasting. When they finish, kids will start unwrapping their presents. That's right, we don't wait until the morning!

During the supper, it's often a point of the discussion who actually brings the gifts. For some, it isn't Santa, as we celebrate the St. Nicholas's Day on December 6. Different regions of Poland traditionally have a different gifter: the Angel, the Christmas Star, Father Christmas (more accurately translated as 'Grandpa Frost') or even Baby Jesus himself.

What's common across the country is the fact that the Christmas Eve supper should include 12 dishes, although the specifics vary from family to family. We decided to take a poll and see what are the most common and uncommon delicacies among our team.

Most of us enjoy fried carp, herring in various forms, sauerkraut with mushrooms, borsch with dumplings and stewed dried fruit. Also quite popular are the mushroom soup and sauerkraut with dried peas. At the same time, there are lots of family-specific dishes. These include fish soup, dumplings, poppy seed dish or cake, salads, gingerbread or fruitcake.

One very specific snack is a Silesian dessert called moczka—a thick pulp made mostly with gingerbread, prunes, raisins, and nuts. It's prepared on some kind of a liquid base, which today is usually dried fruit soup or beer; however, the traditional recipe calls for... fish soup.

It's amazing how similar yet different are our Christmas traditions. Their variety reminds us that if people are so different and interesting within a single country, we can't begin to imagine how beautifully diverse the world really is. We'd love it if you shared your traditions with us.

Wherever you are, and whether you celebrate Christmas or not, let us wish you all the best.

The Wanderlust Team

We're in the running for INDIE OF THE YEAR! Support us in the finals

With your votes, Wanderlust: Travel Stories has qualified to the final stage of the Indie of the Year competition. Thank you! Only 100 games have made it this far.

However, this means we need you again.

The Indie of the Year award is based entirely on a public vote, and the winner will also be determined in a poll. If you think that we deserve this title, you can easily help us get it.

To cast a vote, go to page below and find Wanderlust: Travel Stories in the "Adventure" category. You don't have to register - it takes just one click.

VOTE HERE

If you have already voted, consider sharing this news with friends. Thanks again for your help!

Until next time,

The Wanderlust Team

Dev Diary: Choices and Emotions

Our Goals

In May 2018 we decided to make a story game about travel. We wanted to keep it real, introspective and minimalistic.

To make a game grounded in real experiences we took on board a team of travel journalists, writers, and anthropologists, and put a lot of effort into research, interviews, photographic documentation, etc. This gave us a solid framework for the story, but also limited the range of possible choices.

We wanted to show not the, sometimes boring, logistics of travel but, above all, the feelings and emotions of a traveler. To do this we constructed a cast of characters representing very different ideas about traveling and wrote a collection of stories from their personal perspectives — a kind of interactive memoirs.

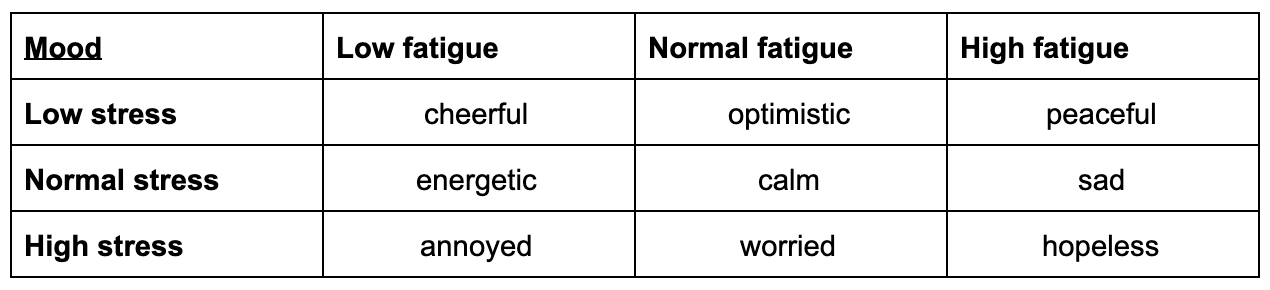

Wanderlust: Travel Stories is a literary experience, and we made sure nothing distracts you away from the text. The static photos and illustrative soundscapes are there just to bring back memories or stir your imagination. The user interface is also very basic, its most important elements are stress, fatigue, and mood — showing the emotional state of the character and its influence on the story. This mechanism is described in the next sections of this text.

On Decisions

In the heart of every good scene is a dilemma the hero must face. By observing the hero in action we learn who they really are. The action changes the situation and creates consequences, often resulting in another dilemma.

What makes games unique, is that the designers set up a dilemma, but it is the player who makes the decision and is responsible for who the hero turns out to be. To make an informed choice the player has to be able to imagine possible outcomes. In well-written stories, the player can also compare the projected consequences with what really happened, and learn.

If this topic interests you, I wholeheartedly recommend John Yorke’s book Into the Woods, on how the learning process in our brain coexist with and shapes the stories we tell.

On Context

If we stick to the above-mentioned rules, every scene should include such elements:

- setting the dilemma,

- presenting options,

- decision,

- delivering consequences.

If we want to make the story interactive, the first thing that usually comes to mind is to present more options. But they branch into many consequences, exponentially exploding the story tree. There are many industry standards to deal with the problem (ex. this great article by Emily Short), and we knew that we needed something very streamlined. Our time, budget and research, gave us a very tight set of constraints. We decided to focus less on shaping the world, and more on experiencing it.

That brings us to a crucial element of any decision-making process: context. Do you want a glass of water? There are two simple ways to answer, to default options: yes and no. Yet the answer would heavily depend on whether you are in a desert, dying of thirst, or on an important meeting, and really needing to go to the loo. There are moments when the context is everything.

So, we decided to highlight the subjective and personal nature of travel, to modify and multiply rather the contexts than the options. To do this, we reached for emotions.

On Emotions

As many travelers would tell you, sometimes the world is what it is, but usually emotions color the perception. When tired or stressed you experience the world differently.

Wanting to show how stress and fatigue influence how we feel about the places we visit, we implemented a very simple emotional simulator. It was based on a model described in Christophe André’s book about moods called “Les États d’âme : Un apprentissage de la sérénité.”

We simplified the model a bit, and this is how it works in Wanderlust: Travel Stories:

Table: stress and fatigue levels shape the character's mood

The player’s decisions, apart from branching the story from time to time, usually influenced stress and fatigue. The resulting mood was being fed back to the story, modifying the context of every following decision.

The idea was to have every scene opening and summary written in at least three (up to nine) versions, reflecting the character’s possible moods. The more important the scene was to the main story arc, the higher emotional fidelity it had. Additionally, some options were available only in certain moods. We did not always manage to do that, but that was what we aimed for.

Case Study: One Night in Paris

As an example, I chose a scene in Paris, one that is not spoilery and designed well enough to dissect in the public. Our hero steps off the train and has his first experience with the capital of France. What he sees and what options are available depends on his stress and fatigue.

The way players approach the available options, depends on the context they were given, or at least that was the idea behind the design.

Low stress, high fatigue, mood: peaceful

When the character is peaceful, he sees Paris “as it is,” just another European city near a train station. The main choice in this scene is how to proceed, whether to take a taxi or walk. Because Tomek is fatigued, an extra option appears “I was hungry.” We can expect that most players will eat something (to regain some strength) and then decide whether to walk or call a taxi.

High stress, high fatigue, mood: hopeless

The situation changes when the character is hopeless. High stress and high fatigue render the world hostile, and the character focus on possible dangers: drunks, shouting, a reeking dumpster. The main call-a-taxi-or-walk choice remains the same, and there are two extra options: “I was hungry,” and “I needed a drink,” the later triggered by high stress. Eating is still a valid option gameplay-wise, but in the presence of a smelly dumpster, many players lose their appetite and just call a taxi to get out of that awful place.

Normal stress, normal fatigue, mood: calm

When a character is calm the place looks normal and the choice boils down to picking the best way to proceed. Curious players will probably take a walk, while the “optimizers” would probably call a taxi to save their strength for the future.

Low stress, normal fatigue, mood: optimistic

An optimistic character sees the city in its most glamorous form, full of light and excitement. It looks inviting, making the taxi seem like a less interesting choice.

The graph of the scene looks like this:

As far as the branching goes, the situation is quite simple — we make a decision, and at the end of the scene we either walk down one branch or sit in a taxi going down another branch of the story tree. Sometimes there are extra diversions available, in the form of short scenes in a bar and/or in a bistro, but they feed back to the main choice.

But when we look at the mood-dependent contexts, the situation gets more interesting. Although the number of outcomes stays the same, the number of personal situations framing the decision multiply. Taking a taxi to escape a hostile environment is a different decision than giving up on an otherwise alluring walk to save strength for another day. A quick snack before a night stroll is something different than a forced meal in a dive near a smelly dumpster.

We learned the nuances of this technique as we went, so not all instances you’ll find in the game, work perfectly, but we found it a great production tool. It allowed us to save on extensive (and expensive) branching we were prone to, and to keep the story within our research-based limits, while allowing for extensive personalization of the events. We set most scenes in the mood-depending context, and as a result, the number of personal decision-making situations available to players became much higher than the actual scene count.

On Personalization

The mood simulator was just a specific, and the most universal, case when we used variables to personalize the story. In short, it worked like this: the main decision in a scene branched the story, but some of the decisions also changed a variable value (be it fatigue, the strength of a relationship with another character, or just noting that a certain event took place). The variable then fed back to scenes down the story-tree, no matter which of the branches we explored.

We used this simple and effective mechanism both to personalize small details of the stories and to decide about the outcomes of whole character arcs.

The details can be as small as whether Henriette is a tea or a coffee person. The first choice the player makes about their favorite beverage reflects on the whole long sailing to Antarctica — with a steaming cup of tea (or coffee) in hand. Sometimes the changes are about people. Depending on how the player directs Adília’s relation with her husband, she talks about him using his name “Jose” or coldly calls him “the husband.” The mechanism is crucial in the story’s finale, when the available options that shape Adília’s future, are gated by variables reflecting her relationships with various people in her life.

Looking Back

We wanted to tell stories that were real and personal, and we knew that we would be working in a small team and within the limits set by our research. Those factors advised against extensive branching of the story (which was our first idea), yet we wanted to keep the experience varied among different players, and we wanted it to feel personal.

The solution we reached for, was to use the player’s decision points not only to branch the story but also to set different variables, which then fed back to the following scenes, modifying them to reflect how the player directed the character.

The most universal and crucial of the variables, were stress and fatigue, which we used to track the mood of the characters. The mood then influenced how surroundings were described, providing changing and personal context for every decision. Thanks to this, using a limited number of story branching points, we aimed to create a significantly higher number of unique decision situations.

We learned how to use the mechanisms as the production progressed, so the implementation is not always perfect, but we believed the idea was interesting enough to share it with you.

I hope you'd find this look behind the scenes worth your time.